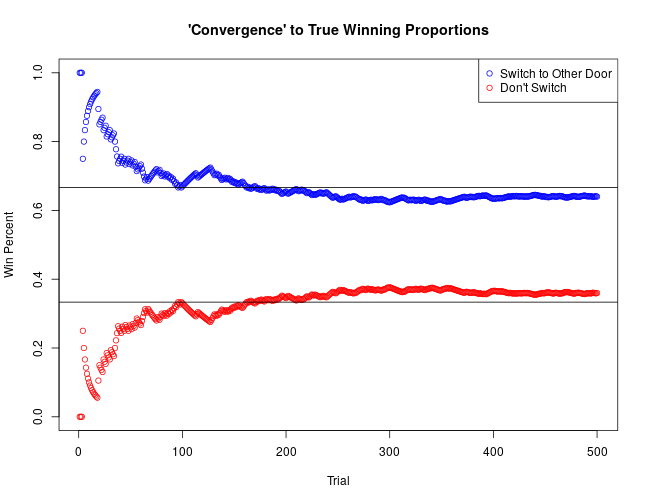

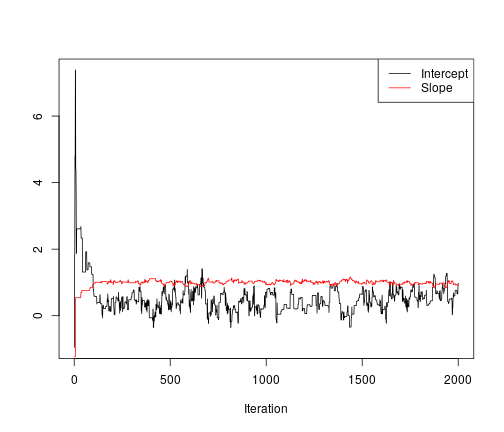

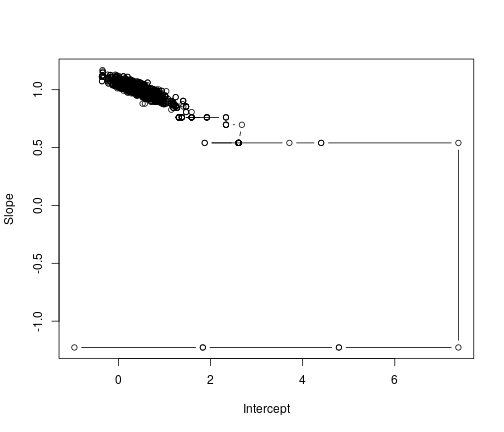

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide # GNU MCSim Tutorial 3 ## Markov Chain Monte Carlo Calibration <html> <div style="float:left"> </div> <hr color='#EB811B' size=1px width=796px> </html> ### Nan-Hung Hsieh ### May 23, 2019 --- # Outline ## 1. Markov Chain Monte Carlo - Principle & Workflow - **Example: linear model** ## 2. `MCMC()` - Working with GNU MCSim & R - **Example: Ethylbenzene PBPK model** ## 3. Population modeling - Single and multi level - **Example: Tetrachloroethylene PBPK model** ??? In this tutorial, we will focus on MCMC calibration. Which means we want to calibrate the model parameters and find the likelihood of the model parameter to fit the data. I will start by introducing the MCMC principle. What is Bayesian? What is MCMC? How do we apply this technique in our modeling process? Also, I will summarise the overall workflow include the content in our previous tutorials. And, I will use the linear model as an example to explain the basic knowledge in MCMC calibration. The second section is to explain how to use mCSim to Run MCMC simulation and use R to analyze and visualize the model output. We will go through the Ethylbenzene PBPK model as an example to demo the full workflow from model verification, uncertainty, and sensitivity analysis and finally demonstrate the MCMC calibration in this case. After the ethylbenzene PBPK model, I'll use the tetrachloroethylene PBPK model to explain how to apply the hierarchical approach to calibrate the parameter in population and individual levels. --- # General workflow ### 1 Model constructing or translating ### 2 Verify modeling result - **Compare with published result** - **Mass balance** ### 3 Uncertainty and sensitivity analysis - **Monte Carlo simulation** - **Morris elementary effects screening** - **Fourier amplitude sensitivity test** ### 4 Model calibration - **Markov chain Monte Carlo** - Diagnostics (Goodness-of-fit, convergence) ??? Here is the review of the general workflow in our modeling process. In the first tutorial, I explain the basic knowledge in PK modeling. We can translate the model code from other programming language to MCSim and conduct the straight forward simulation. We had some exercise to run the model and verify the modeling result through comparing the published data. Then, in the uncertainty and sensitivity analysis, we can apply Monte Carlo simulation with the given distribution of model parameter to exam whether the experiment data can be covered in uncertainty or the distribution of model output. If our data can not cover in the range of our simulation, we might need to figure out which parameters had significant impact on the model output. So through Morris elementary effects screening we can find the influential parameter for specific varibale in our model than we can adjust the parameter range to have better prediction. In addtion, if we have too many parameters that might cause the computational burden in MCMC calibration, we might need to apply the global sensitivity approach to detect the noninfluential parameter and fix this parameter at baseline value. Finally, we can us MCMC algorithm to do model calibration. This is the today's topic as well. --- # MC & MCMC ## Monte Carlo ### - Generate the probability distribution based on the given condition </br> ## Markov Chain Monte Carlo ### - Iterative update the probability distribution, if the new proposed distribution is accepted. --- # Bayes' rule .font200[ $$ p(\theta|y) = \frac{p(\theta) p(y|\theta) }{p(y)}$$ ] `\(\theta\)`: **Observed or unobserved parameter** `\(y\)`: **Observed data** </br> `\(p(\theta)\)`: *Prior distribution* of model parameter `\(p(y|\theta)\)`: *Sampling distribution* of the experiment data given by a parameter vector `\(p(y)\)`: *Likelihood* of data `\(p(\theta|y)\)`: *Posterior distribution* ??? The MCMC is based on the Bayesian rule. In this function, it includes the density of observed or unobserved parameter that is often referred to as the prior distribution in our model, which is p(theta). Also, we have the sampling distribution (or data distribution), which is p(y|theta). This term is used to explain the probability of the observed result that is given by the model parameter. Then, we need to have the likelihood to describe the probability distribution of the experiment data (y). And through this information, the posterior can be estimated by this equation. --- # Monty Hall Problem > Suppose you’re on a game show, and you’re given the choice of three doors. Behind one door is a car, behind the others, goats. You pick a door, say number 1, and the host, who knows what’s behind the doors, opens another door, say number 3, which has a goat. He says to you, ”Do you want to pick door number 2?” Is it to your advantage to switch your choice of doors? > Marilyn vos Savant. 1990. Ask Marilyn. *Parade Magazine*: 16. .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[ <!-- --> ] ??? The famous example of Bayesian rule in real life is the Monty Hall problem. Suppose there is a game show, the contestant has a chance to win a car that is behind the one of three-door, so the probability of winning the car is one-third. But the host gives the contestant the information, he opens the door that is a goat behind this door and asks contest to switch from the chosen door or not. At this time, in this case, the question is changed to what is the probability of winning the car if the contestant switches the choice. It's not the 50/50 probability. The diagram here explains the conditional probability of winning by switching the door. If contestant switches the door, it will have 67% probability to win the game compared with 33% if staying with the original choice. --- # Markov Chain Monte Carlo .font120[ - **Metropolis-Hastings sampling algorithm** ] The algorithm was named for Nicholas Metropolis (physicist) and Wilfred Keith Hastings (statistician). The algorithm proceeds as follows. **Initialize** 1. Pick an initial parameter sets `\(\theta_{t=0} = \{\theta_1, \theta_2, ... \theta_n\}\)` **Iterate** 1. *Generate*: randomly generate a candidate parameter state `\(\theta^\prime\)` for the next sample by picking from the conditional distribution `\(J(\theta^\prime|\theta_t)\)` 2. *Compute*: compute the acceptance probability `\(A\left(\theta^{\prime}, \theta_{t}\right)=\min \left(1, \frac{P\left(\theta^{\prime}|y\right)}{P\left(\theta_{t}|y\right)} \frac{J\left(\theta_{t} | \theta^{\prime}\right)}{J\left(\theta^{\prime} | \theta_{t}\right)}\right)\)` 2. *Accept or Reject*: 1. generate a uniform random number `\(u \in[0,1]\)` 2. if `\(u \leq A\left(x^{\prime}, x_{t}\right)\)` accept the new state and set `\(\theta_{t+1}=\theta^{\prime}\)`, otherwise reject the new state, and copy the old state forward `\(\theta_{t+1}=\theta_{t}\)` ??? Markov chain Monte Carlo is a general method based on drawing values of parameter theta from approximate distributions and then correcting those draws to better approximate target posterior p(theta|y). The Metropolis-Hastings algorithm is a general term for a family of Markov chain simulation methods that are useful for drawing samples from Bayesian posterior distribution. The Metropolis algorithm is an adaption of a random walk that uses an acceptance/rejection rule to the target distribution. In the beginning, it draws a starting point for the initial parameter sets based on the given prior parameter setting. Then, sample the candidate parameter state from a jumping distribution, which is J of theta prime given theta t. The second step is to compute the acceptance probability from the ratio of posterior and jumping distribution. Finally, it uses the acceptance probability and compares with the random number that generates from a uniform distribution between 0 and 1 to determine the proposed parameter vector can be kept or discard in the next iteration. show animation A Markov Chain is a random process that has the property that the future depends only on the current state of the process and not the past. So, it is memoryless. Imagine somebody who is drunk and can move only one pace at a time. The drunk moves with equal probability. This is a Markov Chain where the drunk's future or next position depends only upon where he is at present. --- class: middle .font200[ ## The product of output is not ~~best-fit~~, but "prior" and "posterior". ] ??? In the MCMC process, the pupose is not to estimate the maximun likelihood, but it attemp to continuous construct the probability of the parameter estimation. The posterior in the current iteration will become the prior of next iteration. --- # log-likelihood The log-likelihood function was used to assess the **goodness-of-fit** of the model to the data ([Woodruff and Bois, 1993](https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0378427493901035?via%3Dihub), [Hsieh et al., 2018](https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2018.00588/full#B43)) `$$L L=\sum_{i=1}^{N}-\frac{1}{2} \cdot \frac{\left(y_{i}-\widehat{y}_{i}\right)^{2}}{S_{j[i]}^{2}}-\frac{1}{2} \ln \left(2 \pi s_{j[i]}^{2}\right)$$` `\(N\)`: the total number of the data points `\(y_i\)`: experimental observed `\(\hat{y}_i\)`: model predicted value `\(j[i]\)`: data type (output variable) of data point `\(i\)` `\(S_{j[i]}^{2}\)`: the variance for data type `\(j\)` ??? There is a log-likelihood function that can be used to estimate the goodness-of-fit. This function used the information include ... to estimate log-likelihood. In our study, we used this function to assess the model performance when we apply parameter fixing. The log-likelihood of data can also estimate in MCSim in each iteration. --- # Calibration & evaluation ### Prepare model and input files - Need at least 4 chains in simulation ### Check convergence & graph the output result .font120[ - **Parameter**, **log-likelihood of data** - Trace plot, density plot, correlation matrix, auto-correlation, rank histogram, ... - Gelman–Rubin convergence diagnostics (potential scale reduction factor, `\(\hat{R}\)`) ] ### Evaluate the model fit - Global evaluation (all output variables, `\(y_{i,t}\)`) - Individual evaluation ??? In the model calibration and evaluation process, we need at least four chains to check how good of the convergence of the model parameter sacross these four simulations. Ideally, the posterior should be well-mixing and not easy to distinguish the difference. There are several methods to check the convergence include trace plot, density plot, correlation matrix, auto-correlation, rank histogram, etc. The most widely-used convergence diagnostic is the potential scale reduction factor, which was published by Gelman and Rubin in 1992. After the convergence diagnosis, we can evaluate the model fit through the global method. The MCSim also provide a simple way to quickly check the result through this way. In addition, we can check the individual time-concentration profile and evaluate the model performance. --- # Example: linear modeling .code60[ .pull-left[ **model-file** ```r ## linear.model.R #### Outputs = {y} # Model Parameters A = 0; # Default value of intercept B = 1; # Default value of slope # Statistical parameter SD_true = 0; CalcOutputs { y = A + B * t + NormalRandom(0,SD_true); } End. ``` ] .pull-right[ **input-file** ```r ## ./mcsim.linear.model.R.exe linear_mcmc.in.R #### MCMC ("MCMC.default.out","", # name of output file "", # name of data file 2000,0, # iterations, print predictions flag 1,2000, # printing frequency, iters to print 10101010); # random seed (default) Level { Distrib(A, Normal, 0, 2); # prior of intercept Distrib(B, Normal, 1, 2); # prior of slope Likelihood(y, Normal, Prediction(y), 0.5); Simulation { PrintStep (y, 0, 10, 1); Data (y, 0.0, 0.15, 2.32, 4.33, 4.61, 6.68, 7.89, 7.13, 7.27, 9.4, 10.0); } } End. ``` ] ] --- # The data ```r x <- seq(0, 10, 1) y <- c(0.0, 0.15, 2.32, 4.33, 4.61, 6.68, 7.89, 7.13, 7.27, 9.4, 10.0) plot(x, y) ``` <!-- --> --- # MCMC sampling process .font80[ ``` ## iter A.1. B.1. LnPrior LnData LnPosterior ## 1 0 -0.95484 -1.22704 -3.958099 -4567.137 -4571.095 ## 2 1 1.83302 -1.22704 -4.264131 -3201.785 -3206.049 ## 3 2 1.83302 -1.22704 -4.264131 -3201.785 -3206.049 ## 4 3 4.78650 -1.22704 -6.707952 -2128.378 -2135.086 ## 5 4 4.78650 -1.22704 -6.707952 -2128.378 -2135.086 ## 6 5 7.38065 -1.22704 -10.653380 -1502.173 -1512.826 ``` ] .pull-left[ **Trace plot** <!-- --> ] .pull-right[ **Parameter space** <!-- --> ] --- # Trace plot ```r parms_name <- c("A.1.","B.1.") mcmc_trace(sims, pars = parms_name, facet_args = list(ncol = 2)) ``` <!-- --> --- # Kernel density ```r j <- c(1002:2001) # Discard first half as burn-in mcmc_dens_overlay(x = sims[j,,], pars = parms_name) ``` <!-- --> --- # Pair plot ```r mcmc_pairs(sims[j,,], pars = parms_name, off_diag_fun = "hex") ``` <!-- --> --- # Summary report ```r monitor(sims, probs = c(0.025, 0.975) , digit=4) ``` ``` ## Inference for the input samples (4 chains: each with iter=2001; warmup=1000): ## ## mean se_mean sd 2.5% 97.5% n_eff Rhat ## iter 1500.0000 91.1594 288.9998 1025.0000 1975.0000 10 2.1056 ## A.1. 0.4466 0.0300 0.3002 -0.1278 0.9969 100 1.0407 ## B.1. 0.9980 0.0049 0.0512 0.8949 1.0919 109 1.0352 ## LnPrior -3.2607 0.0039 0.0377 -3.3492 -3.2247 94 1.0412 ## LnData -19.5507 0.0839 1.0927 -22.8720 -18.4954 170 1.0194 ## LnPosterior -22.8113 0.0868 1.1122 -26.0994 -21.7368 164 1.0203 ## ## For each parameter, n_eff is a crude measure of effective sample size, ## and Rhat is the potential scale reduction factor on split chains (at ## convergence, Rhat=1). ``` --- # Evaluation of model fit <!-- --> --- # Demo - linear model ## 1 Single chain testing - **MCMC simulation** ## 2 Multi-chains simulation - **Check convergence** - **Evaluation of model fit** .footnote[ https://rpubs.com/Nanhung/NB_190523 ] --- # MCMC() ```r # Input-file MCMC(); # <Global assignments and specifications> Level { Distrib(); Likelihood(); # Up to 10 levels of hierarchy Simulation { # <Local assignments and specifications> } Simulation { # <Local assignments and specifications> } # Unlimited number of simulation specifications } # end Level End. ``` --- # MCMC() The statement, gives general directives for MCMC simulations with following syntax: ```r MCMC("<OutputFilename>", "<RestartFilename>", "<DataFilename>", <nRuns>, <simTypeFlag>, <printFrequency>, <itersToPrint>, <RandomSeed>); ``` `"<OutputFilename>"` Output file name, the default is "MCMC.default.out" `"<RestartFilename>"` Restart file name `"<DataFilename>"` Data file name `<nRuns>` an integer for the total sampling number (iteration) `<simTypeFlag>` an integer (from 0 to 5) to define the simulation type `<printFrequency>` an integer to set the interval of printed output `<itersToPrint>` an integer to set the number of printed output from the final iteration `<RandomSeed>` a numeric for pseudo-random number generator --- # Simulation types **`<simTypeFlag>` an integer (from 0 to 5) to define the simulation type** `0`, start/restart a new or unfinished MCMC simulations `1`, use the last MCMC iteration to quickly check the model fit to the data `2`, improve computational speed when convergence is approximately obtained `3`, tempering MCMC with whole posterior `4`, tempering MCMC with only likelihood `5`, stochastic optimization --- # Check convergence ### Manipulate (MCSim under R) `mcmc_array()` ### Visualize (**bayesplot**, **corrplot**) `mcmc_trace()` `mcmc_dens_overlay()` `mcmc_pairs()` `corrplot()` ### Report (**rstan**) `monitor()` --- # Parallel  --- # Demo - Ethylbenzene PBPK Model ### Model verification (tutorial 1) **- Compare the simulated result with previous study** ### Uncertainty analysis (tutorial 2) **- Set the probability distribution for model parameters** ### Morris elementary effects screening (tutorial 2) **- Find the influential parameters** ### MCMC calibration (tutorial 3) **- Estimate the "posterior"** .footnote[ https://rpubs.com/Nanhung/NB_190523 ] --- background-image: url(https://i.ibb.co/q5vKKjJ/Screen-Shot-2019-05-13-at-4-43-31-PM.png) background-size: 400px background-position: 70% 30% # Bayesian Population Model .large[**Individuals level**] `\(E\)`: Exposure `\(t\)`: Time `\(\varphi\)`: measured parameters `\(\theta\)`: unknown parameters `\(y\)`: condition the data </br> .large[**Population level**] `\(\mu\)`: Population means `\(\Sigma^2\)`: Population variances `\(\sigma^2\)`: Residual errors .pull-right[ .footnote[ https://doi.org/10.1007/s002040050284 ] ] --- # Population modeling .code60[ .pull-left[ **Individuals level** ```r # Comments of Input-file <Global assignments and specifications> * Level { # priors on population parameters Distrib () Likelihood () * Level { # all subjects grouped Experiment { # 1 <Specifications and data in 1st simulation> } # end 1 Experiment { # 2 <Specifications and data in 2nd simulation> } # end 2 # ... put other experiments } # End grouped level } # End population level End. ``` ] .pull-right[ **Subject level** ```r # Comments of Input-file <Global assignments and specifications> * Level { # priors on population parameters Distrib () Likelihood () * Level { # individuals Distrib () * Level { # subject A Experiment { # 1 <Specifications and data in 1st simulation> } # end 1 Experiment { # 2 <Specifications and data in 2nd simulation> } # end 2 } # End subject A # ... put other subjects } # End individuals level } # End population level End. ``` ] ] --- # Demo - Tetrachloroethylene PBPK Model ## 1 Individuls level - **Population-experiments** ## 2 Subject level - **Population-individuals-experiments** .footnote[ https://rpubs.com/Nanhung/SM_190523 ] --- # Final thoughts MCMC simulation is a computational intensive process for metamodel or big data, one of the important issue today is how to improve the efficiency in the modeling. - If possible, remove or turn-off unnecessary state variable (e.g., mass balance, metabolites). - Re-parameterization ([Chiu et al., 2006](https://rd.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00204-006-0061-9)) - Global sensitivity analysis and parameter fixing ([Hsieh et al., 2018](https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2018.00588/full)) - Parallel computing - Grouped data - Algorithm - Software, hardware, ... --- class: inverse, center, middle # Thanks! </br> question? .footnote[ The slide, code, and record can find on my website: [nanhung.rbind.io](https://nanhung.rbind.io/talk/) ]